1900 – 1959

BLACK: legal events in Oregon | BLUE: legal events in the Oregon State Bar | BROWN: federal events | GREEN: hyperlinks

1900 Yosuke Matsuoka, a Japanese national, graduates from the University of Oregon Law School. He later serves as Japan’s Minister of Foreign Affairs during World War II and is arrested in 1946 for his involvement in preparing Japan for war and inciting his country’s invasion of the Soviet Union. Matsuoka dies in prison before his trial for “war crimes” could take place.

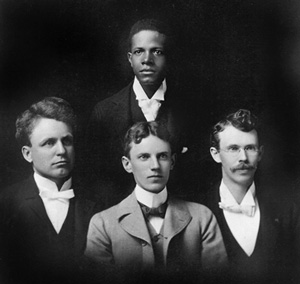

1903 McCants Stewart becomes the first black member of the Oregon Bar Association. A class photograph shows Stewart, originally from New York, standing with his fellow officers in the University of Minnesota law school’s graduating class (1899). After earning additional law degrees, Stewart came to Oregon in 1902.

1907 Seid Back, Jr., graduates from the University of Oregon and in June is the the first known Chinese American admitted to practice law in Oregon. Back also helps found the American Born Chinese Association, organized in 1900 and still in existence, for the purpose of the social, mental, and physical advancement of American-born Chinese children.

1908 The U.S. Supreme Court, in Muller v. Oregon, 208 US 412 (1908), justifies both sex discrimination and usage of labor laws when it upholds Oregon’s restrictions on the working hours of women, based on the state’s interest in protecting women’s health. Though the state wins shorter hours for women and the state’s progressives are happy with the outcome, equal-rights feminists line up against the decision because it retains the separation of the sexes into stereotyped gender-roles as well as restricts women’s financial independence. The Oregon law gives White women more protection, but excludes women of color, food processors, agricultural workers, and white collar educated women. The ruling is criticized because it sets a precedent to use sex differences, and in particular women’s child-bearing capacity, as a basis for separate legislation, supporting the idea that the family has priority over women’s rights as workers. The effects of Muller v. Oregon did not change until the New Deal in the 1930s.

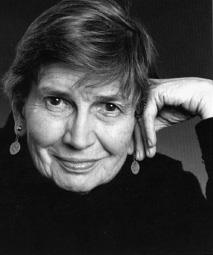

1909 Manche Langley, daughter of a Forest Grove attorney, is admitted to the Bar. She continues to practice—concluding her career as chief deputy district attorney for Multnomah County—until her death in 1963. The Manche Langley Scholarship Fund is conceived in 1963 and established at Lewis & Clark Law School in 1994 to provide support for law students, especially females.

1912 After five previous attempts by suffragists to convince Oregon’s male voters to give the franchise to women, the 40-plus year campaign to give women the vote finally passes. The state constitution had made voting a privilege for White men only and prevented all women and all men of color from exercising that right. Women’s suffrage in Oregon was tied to questions of race and ethnicity from the beginning.

1914 The Portland chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the oldest continually chartered chapter west of the Mississippi River, is founded as a support and advocacy organization for Oregon Blacks.

1914 – 1918 The Great War (World War I)

1915 Oregon Law School moves to Eugene, though some of the faculty remain in Portland and start the Northwestern College of Law, now the Lewis & Clark Law School.

1916 Louis Brandeis is appointed to the United States Supreme Court. As Justice William O. Douglas wrote, “Brandeis was a militant crusader for social justice whoever his opponent might be. He was dangerous not only because of his brilliance, his arithmetic, his courage. He was dangerous because he was incorruptible. . . [and] the fears of the Establishment were greater because Brandeis was the first Jew to be named to the Court.”

1920 Seventy-two years after the Seneca Falls Convention, the 19th Amendment, giving women the right to vote, is ratified. The Amendment reads: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.”

1920s The Oregon membership of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) grows to 200,000—nearly one in four Oregonians—creating an atmosphere of fear among, and intolerance of, minorities in Oregon.

1922 Takao Ozawa files for United States citizenship under the Naturalization Act of 1906, which allows White persons and persons of African descent or African nativity to naturalize. He attempts to have Japanese people classified as White. The Supreme Court, in Takao Ozawa v. United States, 260 US 178 (1922), finds that only Europeans are White, and therefore the Japanese, because they are not European, are not White and instead are members of an “unassimilable race,” lacking provisions in any Naturalization Act.

1922 Beatrice Cannady becomes the first Black woman to graduate from Portland’s Northwestern College of Law. She is never admitted to the bar, but goes on to represent clients in court. An outspoken civil rights advocate, Cannady successfully advocates for Black children who are denied attendance in Oregon schools.

1922 Metta Boughman Beeman, a 1921 graduate of the Northwestern College of Law, is hired as the first woman in the Office of General Counsel at the Veterans Administration.

1922 After World War I, and concerned about the influence of immigrants and “foreign” values, several states look to public schools for help. Some adopt laws designed to use schools to promote a common American culture. On November 7, 1922, Oregon voters pass an initiative aimed at eliminating parochial (including Catholic) schools and requiring Oregon children —with some exceptions—between eight and sixteen years of age to attend public school. The Sisters of the Holy Names sue Oregon Governor Walter Pierce, alleging that the initiative-amended Oregon Compulsory Education Act “conflicts with the right of parents to choose schools where their children will receive appropriate mental and religious training, the right of the child to influence the parents’ choice of a school, the right of schools and teachers therein to engage in a useful business or profession.” The Sisters’ case asserts that the State violates specific First Amendment rights, such as the right to freely practice one’s religion. Pierce, Governor of Oregon, et al. v. Society of the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary, 268 US 510 (1925), is decided by the U.S. Supreme Court, negating the amendment to Oregon’s Compulsory Education Act and significantly expanding coverage of the Due Process Clause in the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. The decision is a triumph for tolerance and will be cited as a precedent in more than 100 Supreme Court cases.

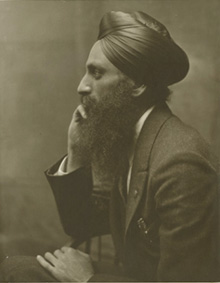

1923 In United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind, 261 US 204 (1923), a case originating in Oregon, the Supreme Court decides that Bhagat Singh Thind, an Indian Sikh—who argues that, as a high-caste Indian, he is “Aryan” and, therefore, “Caucasian”— is also ineligible for naturalization under the terms of the Naturalization Act of 1906.

1924 President Calvin Coolidge signs the Immigration Act of 1924. The act is a federal law that limits the annual number of immigrants who may be admitted from any country to 2 percent of the number of people from that country who were already living in the United States in 1890. By granting naturalization only to “any alien being a free white person,” the law is aimed at further restricting the immigration of Southern and Eastern Europeans, among them Jews who had migrated in large numbers since the 1890s to escape persecution in Poland and Russia, as well as prohibiting the immigration of Italians, Middle Easterners, East Asians, and Indians.

1925 The National Bar Association is established as the “Negro Bar Association” after several African-American lawyers are denied membership in the American Bar Association.

1926 A group of Portland-area women forms the Women Lawyers Association of Oregon. Membership includes Manche Langley, Cecelia Gallagher, Frances Cummings, Gladys Everett, and Dorothy McCullough Lee, among others.

1926 Mary Jane Spurlin is the first woman in Oregon to become a judge. She is initially appointed, but within seven months she is defeated in an election by a man. She later serves as a deputy district attorney.

1926 Oregon repeals its Exclusion Law, which barred Blacks from the state, by amending the state constitution to remove it from the Bill of Rights.

1928 As a representative, Dorothy McCullough Lee becomes the first woman attorney elected to the Oregon Legislature.

1931 Dorothy McCullough Lee and Gladys M. Everett establish what is believed to be Oregon’s first all-women law firm.

1935 Gladys M. Everett becomes Portland’s first woman municipal judge (pro tem).

1935 During a period of labor unrest and continued discrimination along racial lines, and led by attorneys C.E.S. Wood, William U’Ren, and Gus Solomon, along with several leaders from education, publishing, and the ministry, the Oregon chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union is formed to defend Oregonians’ civil liberties.

1935 The Oregon Bar Association ceases to exist due to the combined effects of its lack of success in its legislative endeavors and the efforts to reshape the public’s perception of the legal profession, and the Great Depression of the 1930s. The Oregon legislature creates the Oregon State Bar, membership in which is a condition of the right to practice. The state struggles through the Depression and its attorneys struggle to make a living.

1936 In an early effort to reach out to the larger community during the difficult Depression years and provide aid to the unemployed who needed help with legal problems, the Oregon State Bar’s Board of Governors establishes a legal aid bureau. The bureau concentrates on giving legal assistance in garnishment, forcible entry, and wrongful detainer cases.

1939 At the request of the American Bar Association, the Oregon State Bar appoints a Committee on Civil Rights. During the course of World War II, the Committee investigates issues of prisoners’ rights and the case of Robert E. Lee Folkes, an African American convicted and executed for murder.

1939 During WWII Oregon’s African-American population grows substantially—in Portland increasing from 2,565 in 1940 to 25,000 in 1944. Over 7,000 “non-White” workers are employed in the Portland shipyards. Although Kaiser Brothers promises good jobs, local unions resist integration. Many help-wanted notices specify “White only.” After pressure from the NAACP, the Kaiser Brothers, and a federal inspection team, as well as a reprimand from President Roosevelt, the unions compromise. More skilled jobs are opened to Blacks, but only for the duration of the war. Blacks are allowed to work in union-controlled shops and be paid union wages, but are denied union benefits. To accommodate the influx of workers, a new town is built in the lowland area adjacent to the Columbia River just north of Portland. First called Kaiserville and then Vanport, it becomes—during the 1940s—the world’s largest housing project, with 35,000 residents and making it the second largest community in Oregon. With this rise in diversity in populations came signs throughout Portland: “We Cater to White Trade Only.” Most Black residents remain after the war, building the foundation for what will become a strong African-American community.

1939-1945 World War II

1942 Following the United States’ entry into World War II and just two months following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Executive Order 9066 is issued and Japanese Americans are rounded up and sent to internment camps.

Oregon State Bar member Minoru Yasui, a graduate of the University of Oregon law school, objects to the order and breaks the curfew imposed on Japanese-Americans. He goes to trial and is ultimately stripped of his citizenship. In Yasui v. United States, 320 US 115 (1943), the Supreme Court upholds the constitutionality of curfews used during World War II when applied to citizens of the United States. Despite a lifetime of effort, Yasui’s case is never reversed.

1943 With many of the state’s male attorneys serving in the armed forces, Jeannette Marshall breaks through the law-firm barrier to women attorneys and becomes the first woman associate at a major Oregon law firm Kerner, Young, McCullough, now Lane Powell.

1944 Executive Order 9066, issued early in World War II, allows military officials to compel all persons of Japanese ancestry, regardless of citizenship, to relocate from designated areas on the West Coast into desolate inland “internment camps.” Japanese-American Fred Korematsu challenges the order, arguing that it violated the Equal Protection Clause. The Supreme Court’s 1944 opinion in the case, Korematsu v. United States, 323 US 214 (1944), is now widely regarded as reaching an indefensible outcome, but doing so in a way that ultimately proved to be of great benefit to racial, ethnic, and religious minorities. The court held that a law that discriminated against a racial group was “immediately suspect,” and the law would be unconstitutional unless it could survive the “most rigid scrutiny.” That principle evolved into the so-called “strict scrutiny” standard: laws that discriminate against racial and other minority groups are constitutional only if they are narrowly tailored to achieve a compelling government interest. That level of scrutiny has been called “strict in name, but fatal in fact,” and the number of cases in which a racially discriminatory law has survived can be counted on the fingers of one hand. Unfortunately for Korematsu, his case was one of them. The Court held in a split opinion that the “Exclusion Act” was, in fact, necessary to promote the compelling interest in national security, and there were no less discriminatory ways to accomplish that objective. Although the actual holding of Korematsu has never been overruled by the Supreme Court, Korematsu’s conviction was vacated by a federal district court in 1984 and, in 1988, Congress enacted a law formally apologizing for the internment camps and providing reparations. “Strict scrutiny” survives as a bulwark of protection against discriminatory government action.

1945 Former Japanese-American internees begin to return to their old homes and are often met with open hostility by White neighbors. Some find their homes looted and their orchards vandalized while others endure boycotts of their fruits and vegetables or must endure racial slurs and threats. Despite the many instances of blatant racism, intimidation, and hatred, some Oregonians welcome and support the returning Japanese Americans.

1946 The Oregon State Bar’s Committee on Civil Rights reviews the progress of the American Civil Liberties Union’s (ACLU) investigation of the federal Justice Department’s mass deportation of Japanese aliens and Japanese-American citizens during the war. The Committee also recommends that legal action be taken against the City of Portland’s “after hours” ordinance, which gives the police the right to arrest any person whose explanation does not satisfy them when questioned on the street during the nighttime.

1948 The Queen’s Bench is founded by women lawyers from the Portland area with the stated purpose of the “promotion of professional advancement, comradeship, and good fellowship among women members of the legal profession.” One of the organizers is Helen F. Althaus, a law clerk for U.S. District Court Judge James Alger Fee. She is the first woman to serve as a law clerk to a judge in Oregon. When she joins a law firm following her clerkship, she is told that only her initials will appear on the firm’s door because it was feared that “a woman’s presence might alienate clients.”

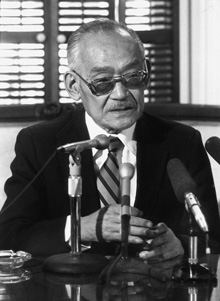

1949 Having established a reputation as an attorney fighting for civil rights and upon his appointment by President Harry Truman, Gus Solomon becomes the first Jewish judge of the United States District Court for Oregon.

1951 Insurance surcharges for non-White drivers are removed from Oregon law.

1953 Representative (and future Governor and U.S. Senator) Mark Hatfield leads the efforts in the Oregon House of Representatives to secure passage of Oregon’s Civil Rights Bill. With Governor Paul Patterson’s signature, Oregon becomes the 21st state in the union to pass legislation outlawing discrimination in public places. The bill ensures “[a]ll persons within the jurisdiction of this state shall be entitled to the full and equal accommodations, advantages, facilities and privileges of any place of public accommodation, resort or amusement, without any distinction, discrimination or restriction on account of race, religion, color or national origin.”

1953 Congress adopts Public Law 280, giving state governments the power to assume jurisdiction over Native American reservations, which had previously been excluded from state jurisdiction. Oregon and five other states are immediately granted criminal and civil jurisdiction over Native American lands within the state. The Warm Springs Reservation is exempted from the transfer of jurisdiction. The law requires neither the consent of nor consultation with the affected tribes.

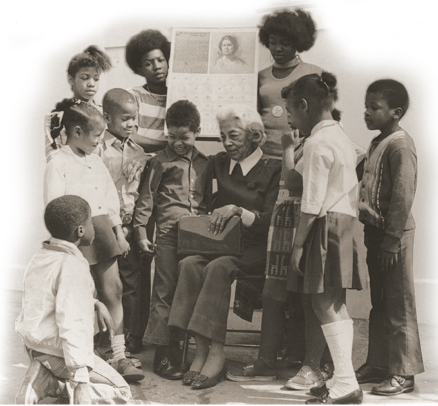

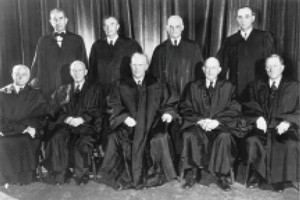

1954 The United States Supreme Court unanimously decides Brown v. Board of Education, 347 US 483 (1954), outlawing segregation in public schools and marking the beginning of new efforts to establish rights for Americans of color. The case was argued by NAACP attorney Thurgood Marshall, who will be appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1967. African-American psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark’s 1940s experiments using dolls to study children’s attitudes about race factored into the Court’s decision. In the Court’s ruling, Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote: “To separate [Black children] from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely to ever be undone.”

1954 Congress passes the Klamath Termination Act, a measure authorizing the sale of reservation lands and establishing procedures for terminating all federal relationships with the Klamath Tribes. The same year, Congress passes the Western Oregon Indian Termination Act. This law terminates federal recognition of sovereign, tribal status as well as supervision over the trust and restricted property of numerous Native American bands and small tribes, all located west of the Cascades. Federal supervision of 62 Oregon tribes is terminated. Millions of acres of timber are transferred out of tribal control and into private hands. The economic and social effects for the tribes prove devastating.

1954 H.J. Belton Hamilton is appointed Oregon’s first African- American Assistant Attorney General and goes on to influence every important civil rights law that passes the Oregon Legislature in the 1960s and 1970s. In 1970 he is appointed as a Federal Administrative Law Judge, a position he holds until retirement in 1995.

1956 Hattie Bratzel Kremen is the first woman elected as a district attorney (Marion County) in Oregon.

1957 The Oregon State Bar establishes a Committee on Legal Rights of Indians, which takes up a number of issues relating to Oregon Native American tribes, including the Klamath County Bar Association’s fee schedule and the need for changes in Oregon laws regarding guardianship and probate as they applied to Native Americans. Although the committee studied these matters, it takes no action. Advocacy for tribal governments and individual tribal members is ultimately handled by independent attorneys and the courts.

1959 Oregon voters finally ratify the 15th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, though since 1870 federal law has superseded a clause in the Oregon State Constitution banning Black suffrage.